Best Practices: Using Machine Translation for Chinese copy

It’s often tempting for companies to use Machine Translation for languages like Chinese*, which they may not be familiar with. Natural Language Processing (NLP) is the most successful model for Machine Translation right now. And it’s improving rapidly, as AI models are learning to “think” for themselves (kind of…).

*Note: In this article, “Chinese” means Mandarin Chinese.

The problem, basically, is that human language and communication is complex and nuanced. Different people will say the same thing in different ways — we use different emphasis, some enjoy wordplay and quirky metaphors, and we all like to innovate when expressing ourselves freely. This is really hard for machines to both understand and replicate — it’s hard for them to select which translation will resonate best with humans. This is why ChatGPT generated text can feel a little bland or somehow, soulless.

All languages have rules, many can be taught, but there are some that most of us have internalised unconsciously. A famous example of this in English, is the ‘opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose’ rule for descriptions. Most native english speakers would struggle to formulate this rule, but we would all instantly recognise that “the beautiful, green, vintage car” is correct, whereas the “the vintage, green, beautiful car” is clearly not.

Of course, an AI could learn this rule, but there are many other rules regarding sentence structure — in sentences that are more complex than a string of adjectives — which are harder to define. One standard practice is to ask machines to translate from Language A to Language B and then back to Language A. This is useful training, but of course, there are also different, equally correct, ways to translate something.

Machine Translation and Chinese

In some ways, Chinese is more simple than other languages. Unlike Romance languages, there’s no genders. Also, there’s no cases and no tenses — the tense is understood through context. The use of honorifics is minimal, unlike Japanese. Chinese notably has a considerable number of characters — around 50,000 — but of course, this is no problem for a computer to learn.

However, the interaction between characters can be very complicated, and a specific combination of characters can create a different meaning (concept or word). The tones of the language often determine meaning, it’s sometimes necessary to see the whole context in order to correctly understand the ‘when’ of the text (remember, no tenses!). We recommend to translators that they first familiarise themselves with the document as a whole, before beginning translation.

Some other issues to consider:

Word order

The word order will often change in translation, this is common. And this should always be considered when translating slogans or taglines. Your designer may have chosen to put the first keyword in a different colour, or play with the shape (typography) of the slogan. This may not work in Chinese, and should certainly be brought to the attention of the designer. Furthermore, it is often wise to break up longer, more complex sentences into smaller chunks which can be easier to communicate.

Chinese characters are logograms

Chinese characters can be combined together to form an entirely new meaning, and the new ‘word’s’ meaning is dependent on context and placement. Here’s an example: 開 in Cantonese translates as “to open something”, while 心 signifies “heart.” When joined together, we have the expression “to open your heart,” (開心 ). And finally, when combined as a word, the meaning of the word is “happy.” Simple, right?!

Idioms and metaphors

All translation should be carried out by someone translating into their native language. This is especially important regarding Chinese, as this language is full of curious (and lovely) idioms! It’s important that your translator understands the hidden meanings behind them.

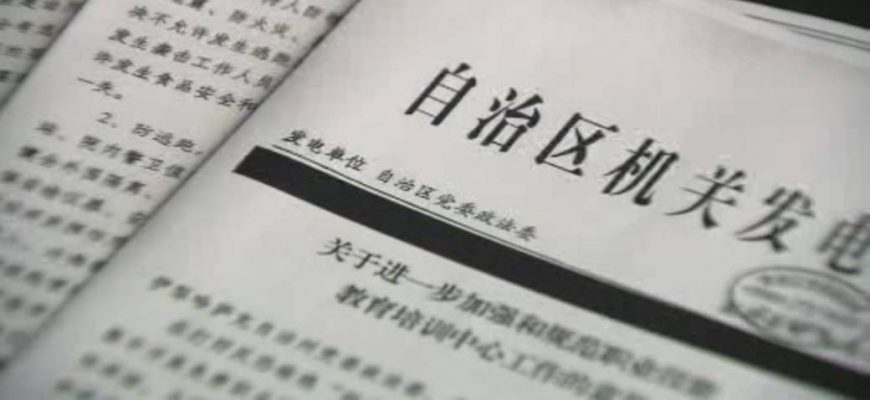

Scripts

There is more than one Chinese script! Different regions use (some) different characters. We wrote another blog post on this just recently — it’s here: Traditional or Simplified Chinese?

Fonts

Just like Latin scripts, Chinese fonts will convey a different style and tone. It’s important to try and match the look and feel of the font when translating. Chinese doesn’t use italics, so emphasis should be conveyed by stroke weight. Early in the design stage, it’s worth considering how many weights your chosen font offers.

Human input

A human translator instinctively understands style, tone and nuance. While there is always a place for machine translation (for internal or data-driven documents, where style is not so important); and while MTPE (Machine Translation Post-editing) can deliver good results — we would always recommend a human translator to send the precise message, and to deliver the right mood!